His future is up in the air after chasing the Olympic dream — and coming away with bronze — what’s a gymnast to do? Run away with the circus, of course

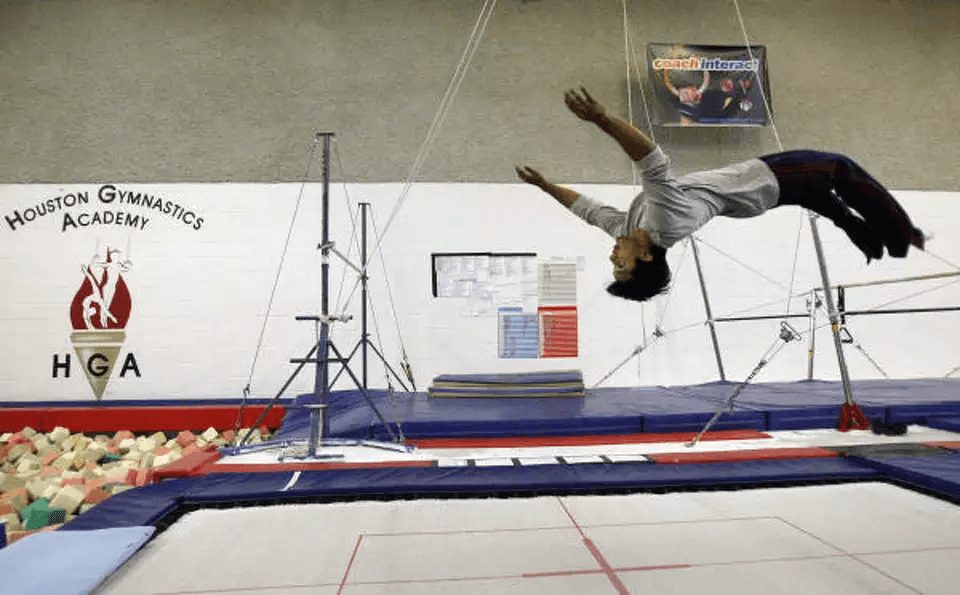

Up and around, up and around, Raj Bhavsar swings and then stops, holding his chiseled 5-foot-3-inch frame high above the bar like the hands of a clock at midnight. Then a giant swing, all the way around the high bar. Then another. Swing and swing and swing and whoosh — he lets go, launching himself high into the air and then down, vanishing into a pit of foam.

The Olympic bronze medalist, a compact, 121-pound bundle of power, emerges in this Houston gym on a fall afternoon, smiling, scanning his surroundings as he begins powdering his hands and preparing for another go. Other athletes are training nearby, rotating over pommel horses and vaulting themselves high into the air. They are chasing the Olympic dream.

Bhavsar, standing shirtless under the high bar, is not. At 30, his time as a competitive gymnast is over, having ended soon after he helped the U.S. earn a bronze medal in the 2008 Olympic Summer Games. Some might say he shouldn’t be here. Now is the time to move on. Time to find your real career. Easier said than done, he thinks.

He looks up at the bar and considers a change to his routine. Maybe he should add a pirouette, or an extra flip? Maybe he should alter the rotation on his release? Maybe, he thinks, that’s what they’ll want at Cirque du Soleil.

Yes, he says later, trying to temper the smile sweeping across his face, “Raj is going to the circus.” It’s an exciting step, he says of his two-year contract to be an acrobat in the company’s newest fixture, a $95 million Hollywood-themed endeavor set to open next summer at the Kodak Theater in Los Angeles. But a step to where?

Gymnastics had become more than just an activity for Bhavsar – it was the joy of his life, the obsession that took over as he meticulously deconstructed and then rebuilt himself into an Olympian.

But what happens when he can’t do it anymore? What happens when he is forced to move on from the flipping and jumping and swinging?

“The challenge then becomes not just doing something with your life, but actually trying to find something that you can fall in love with again,” Bhavsar said. “To me that’s the mission now.”

Bhavsar was 4 when his mother lost him in her west Houston home. She thought he was in the kitchen, but didn’t see him and went to look elsewhere, calling to him in the hallway and the living room. When he called back from the kitchen, Surekha Bhavsar was confused.

“He was sitting on the refrigerator,” she said.

The Bhavsars grew used to seeing such things from their son. He would hang and swing from turnstiles in stores and pull himself up onto kitchen counters using only his arms. They took note of his strength but didn’t think anything of it. When they enrolled Bhavsar and his older brother, Sujit, in gymnastics that year, they did it on a whim.

For Bhavsar, it was an incredible release, an outlet for his instinctual desire to jump and climb and swing. “I just remember thinking, ‘This is the most fun thing in the world,'” he said.

By the time he was 9, coaches recruited Bhavsar to competitive teams. He gradually gained regional and national attention, traveling to camps and clinics around the country. When Tom Meadows began coaching Bhavsar at 13, he saw Olympic potential. “If you dream up a gymnast, he had the attributes that it took,” Meadows said.

In the years that followed, Bhavsar progressed on a trajectory he thought was destined for the 2004 Olympic Summer Games. He moved from the junior national team at 15 and then to the senior national team by the time he was a senior at Mayde Creek High School. Along the way, he helped Ohio State University to a national championship and the U.S. to silver medals at World Championships in 2001 and 2003. When he arrived at the 2004 U.S. Olympic Trials, he was booming with confidence. But that was when he began to unravel.

There was an error, minor but unexpected. He had launched himself off of the vault, rotating in the air and spotting his landing, but when his feet hit the ground, so did his hand. Then another error, on the floor exercise. Still, he performed well, winning the rings competition, then finishing fourth in the all-around standings. With six men chosen to the national team, he expected to be competing in Athens. Days later, in a conference room at a hotel in Colorado Springs, Colo., Bhavsar heard gymnastics officials announce six names, none of them his. Then this: “Alternate.”

He stood and rushed out of the room, grunting the word to his coaches outside. “Alternate,” he said.

The result sent Bhavsar into a spiral of anger, hate, depression, doubt. For months, he tried to forget gymnastics, staying away from the gym that reminded him of his failure in 2004. His friends, family and coaches grew concerned.

Finally, after more than a year away from gymnastics, Bhavsar found himself reconnecting with the sport he loved. He started training again and gaining confidence. Another run for the national team seemed possible. But even then, no performance on the vault or the parallel bars could shake away the demons that plagued him, the doubts that clouded his mind no matter how hard he tried to will them away.

You’re not that good at gymnastics. You’re too old. You don’t belong in this sport. They won’t pick you.

It was a look in the mirror that changed him. He had failed to make the national team for a winter competition in 2007, nine months before the 2008 Olympic Games, when he forced a hard stare into his reflection, looking deep into his eyes. “Instead of being a victim of circumstance and letting life kind of roll over me it was more like, ‘No, I’m not going to let things affect me if I’m the one who controls that,'” Bhavsar said. “No matter what happened in the gym or outside of the gym, I was going to be steering the ship.”

Bhavsar consulted a sports pyschologist and started documenting his doubts in a journal. He studied techniques for creating optimism, devouring motivational books, trying to bend his mind toward his goal. He practiced yoga three times a week and looked in the bathroom mirror or sat in his room, repeating the same line to himself, over and over and over.

I am on the 2008 Olympic team. I am on the 2008 Olympic team. I am on the 2008 Olympic team.

He filled nearly 100 pages with the line.

He chronicled each doubt that crossed his mind, then wrote down positive thoughts to counter them. “I’m not good enough” became “I’m more than enough in life.” “I’m too old” turned into “I can have anything in life if I choose to work for it.”

“A lot of the things I was doing felt really ridiculous, like talking to myself in the mirror, but it was in these books for a reason,” he said. “When I kept reading, I kept seeing a pattern in all of these books … I knew it was absolutely ridiculous but I was going to do whatever it took.”

It almost worked.

Bhavsar was back at the U.S. Olympic Trials in 2008. Filled with renewed confidence, he finished third in the all-around competition, falling two-tenths of a point short of an automatic berth to the Olympic team. Again, he found himself in a conference room listening to the team selection. Again, he didn’t hear his name. “Alternate,” they said.

Bhavsar rushed out of the room. He approached his mother with the news.

“Let’s just get out of here, Raj,” she said, furious about the decision. “Don’t accept being an alternate. Let’s just leave.”

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I know in my heart I did well. How are you?”

Three weeks later, the day before the gymnastics team left for Beijing, Bhavsar got a call while he was training as an alternate. Paul Hamm, the 2004 gold medalist, was injured and would not be able to compete. Bhavsar would take his place.

In the days that followed, Bhavsar and a team of Olympic rookies surprised the international gymnastics community with a bronze medal performance. As he stood on the podium, looking down at his medal, he couldn’t stop smiling. The lesson, he said, was clear.

“Never give up.”

At a dinner party celebrating the Hindu holiday of Diwali, Bhavsar sat among relatives and family friends and spoke passionately about a visit to India, where he went in 2009 to place his medal around his grandfather’s neck. While there, he offered a plan to Indian sports ministers to help take gymnastics there to the next level. They weren’t interested.

He pursued other second careers such as motivational speaking. But so far Bhavsar has only been able to dedicate his life to one thing. And, at least for the near future, he still will.

Cirque du Soleil, which employs 10 other Olympians out of its more than 1,600 performers, will be a fitting transition, he said, perhaps to choreography or another entertainment-related venture.

Although he jokes about participating in a circus – his friends giggled as they queued up Cirque du Soleil music during workouts in Houston – the chance to continue jumping, climbing and flying in ways that are more fluid than competitive gymnastics brings a boyish grin to his face.

His ability and innovation – Bhavsar created two gymnastics maneuvers that were sanctioned for competition and named after him – made him a good fit for the company, said Stacy Clark, an acrobatic talent scout for Cirque du Soleil. Bhavsar is the company’s only U.S. Olympian and is currently participating in rehearsals in Montreal.

Still, moving beyond gymnastics, maybe to another career altogether, will be a challenge to solve in the years to come.